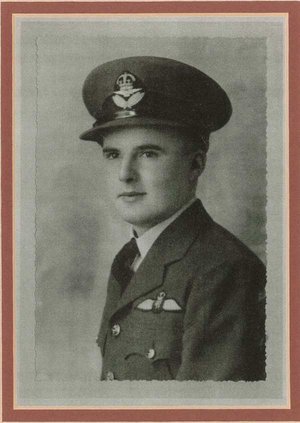

Gordon King Pond

Who is Gordon King?

Gordon King, a 99-year-old Second World War veteran who dodged death several times during war, is honoured on Saturday, June 22 as the City unveils streets and a pond named after him in the new Keswick subdivision. King is surrounded by three of his children: Richard (left), Cathy, and Chris (right).

Plaques surround Gordon King Pond in the Arbours of Keswick development in southeast Edmonton. King, a 99-year-old Second World War veteran who dodged death several times during war, was honoured on Saturday as the city unveiled streets and a pond named after him.

City, developer unveils pond and streets named for POW who missed his great escape

EDMONTON JOURNAL - JANET FRENCH

Developer Rohit Group and local politicians honoured decorated Second World War Royal Canadian Air Force veteran Gordon King with a southwest Edmonton subdivision covered with his namesake

Updated: June 22, 2019

A humble and jovial man, Gordon King doesn’t like any fuss.

However, accolades were unavoidable Saturday as developer Rohit Group and local politicians honoured the decorated Second World War Royal Canadian Air Force veteran with a southwest Edmonton subdivision covered with his name.

On Saturday, in front of a fountain spurting out of Gordon King Pond, near King Vista SW, speakers recounted the 99-year-old Edmontonian’s wartime, volunteer and community contributions.

“I’m sure he’s wondering what all the fuss is about,” his son Chris King said as his father sat nearby in a wheelchair, bundled with blankets.

In the war, King cheated death several times — first in 1942 when he survived his plane being shot down over Germany. When he ejected from the plane, his parachute bag was on incorrectly, and he fell, headfirst, into a tree.

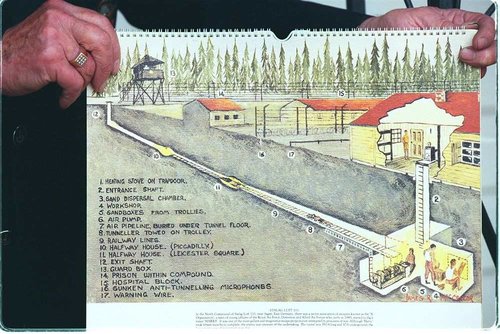

He was captured by the Germans and became a prisoner of war for three years at Stalag Luft III camp. In 1944, he was one of a group of POWs who began digging tunnels to flee, as recreated in the 1963 hit movie, The Great Escape.

Luckily, he never got his chance to escape through those tunnels, as the Germans murdered 50 of the 73 soldiers they recaptured.

Tireless volunteer

After his release from camp in 1945, he reunited with his wife, June, in Winnipeg. The family moved to Edmonton in 1965.

Politicians lauded King’s work with the Rotary Club, the YMCA, the ex-POW association and his Anglican church.

“Mr. King was many things to many of us — a devoted husband, a loving father and a proud Edmontonian who gave so much to make our city a better place,” Minister of Municipal Affairs and Edmonton-South West MLA Kaycee Madu said.

What Chris King remembers best about his father’s younger years are the little things he did to help the people around him — umpiring little league games when none of his children played baseball, for instance. He fixed neighbours’ bicycles, shovelled their snow and visited friends in hospital when they were sick.

Explaining some of his history and contributions are plaques installed next to a footpath that runs the length of the pond in the still-under-development Arbours of Keswick subdivision.

“So often, we go into neighbourhoods that are named for particular people, so it’s great to take this extra step to truly understand this man, his contributions and the legacy that will continue to inform our community,” Coun. Tim Cartmell said.

Gordon King’s son Richard, who lives in Winnipeg, said he can’t wait to bring his children to the neighbourhood to show them the places named in their grandfather’s honour — King Vista SW, King Wynd, King Landing SW and King Gate.

“It’s quite remarkable,” he said.

“It’s overwhelming, quite frankly. Proud is not even the right word, of my father. It’s just amazing,” he said. “This is a legacy that will obviously live forever.”

Gordon King holds the sign for King Vista, a street in the Keswick community that has been named in the veteran's honour.

Southwest community names streets, pond after Second World War veteran

Alex Antoneshyn, Digital Journalist, Published Saturday, June 22, 2019 1:49PM MDT

A pond in southwest Edmonton was dedicated Saturday to a Second World War veteran in recognition of his service and generous support of local and sports communities.

The Arbours of Keswick community held a ceremony on Saturday for Gordon King Pond, and streets King Vista SW, King Wynd, King Landing SW and King Gate, all of which were named in honour of 99-year-old Gordon King.

King served in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War, surviving as a prisoner of war in Stalag Luft III after his plane was shot down over Germany in 1942. He helped dig three escape tunnels out of the camp—which has become known as “The Great Escape”—but narrowly missed his window of opportunity when the tunnels were discovered the night he was set to leave.

After moving to Edmonton in 1965, he contacted other ex-prisoners of war to form the Edmonton branch of the Ex-POW Association. In 2006, he received a Minister of Veterans Affairs Commendation. King also served in the Canadian military, the YMCA, and volunteered with the meals-on-wheels program, among other things.

"He’s (been) the president of so many groups and volunteer associations. Anytime something came to Edmonton, he’d volunteer for it,” said his daughter, championship curler Cathy King.

She attended the service with her father and other family members.

“He probably forgets what he’s done, he’s 99 years old!" she joked. "But he’s an amazing man. ... He’s taught us how to be part of the community, how to volunteer, how to help out, how to be leaders."

The dedications, which were announced by the city in 2016, are considered an honour by King and his family.

“We really are just so thankful the city has recognized him for doing all those things over the years," his daughter said.

There are plaques around the pond outlining who Gordon King is and his contributions to the community.

Edmonton pond named after WW2 veteran who was prisoner of war

By Julia Wong, Digital Broadcast Journalist Global News

WATCH ABOVE: A pond in southwest Edmonton was dedicated to Second World War veteran Gordon King, who was also a prisoner of war. But as Julia Wong reports, his family hopes his legacy goes beyond what happened during the war.

A pond and several streets in southwestern Edmonton now bear the name of a Second World War veteran and former prisoner of war.

Gordon King, 99, was honoured Saturday at the dedication of the Gordon King Pond in the Keswick neighbourhood. His daughter, two sons and grandchildren accompanied him at the ceremony.

“He’s very humble. He just doesn’t understand why they would do something,” said daughter Cathy King with a smile.

“He feels he’s just an ordinary person.”

But King has lived an extraordinary life. A pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force, King’s aircraft was shot down by the Germans. He was captured and spent three years as a prisoner of war.

View photos in the gallery below:

During that time, King participated in The Great Escape where he and fellow prisoners of war dug tunnels in hopes of escaping the prison camp.

“While participating in the digging, Gord played many roles such as the lookout man and ‘the dish,’ taking excavated sand to the entry point and handing it off to a dispersal man. He and another prisoner also stole electrical wire that would replace the oil burning lamps in the tunnels,” reads a handout from the City of Edmonton naming committee, which recommended the pond be named after King.

“Gord was operating the air pump on the evening of the escape, and waiting to be the 141st officer of the 200 men who planned to escape, but only 76 officers made it out of the tunnel, three of which escaped before being discovered by a German solider.”

King remained at the prison camp until 1945. After he returned from the war, he worked in Winnipeg before moving to Edmonton, where he became active in the community with the YMCA, Rotary Club and the Freemasons.

“This is a real honour – to have a street and a pond named after you in the City of Edmonton is fantastic,” Cathy said.

She said she hopes Keswick residents who walk in the seven-acre natural space reflect on the importance of community.

“Community is a big thing for [my dad],” Cathy said. “He needs to know people should get involved in their community and help out and volunteer.

“Hopefully we’ll never have to deal with [war]. He doesn’t feel like he’s a hero in that part of his life, but when you’re involved in your community, that’s really important.”

Several plaques dot the pond, providing information about King and his contributions to the community.

“My dad is the kind of guy everyone would want as a neighbour,” son Chris said. “He was the kind of guy who would lend you a tool or lend you a hand.

“He helped make the neighbourhood a better place to live, and I think it’s wonderful his name is associated with this terrific new community.”

King now lives in a senior retirement home but his family hopes to bring him to the pond when they can.

“I think it would be nice to bring dad here for some walks while he’s still alive. I’m hoping to,” Cathy said.

From the Edmonton Journal's archives: A prisoner of war counts himself lucky after missing his great escape

EDMONTON JOURNAL - AINSLIE CRUICKSHANK

On July 13, 2016, the city informed Second World War veteran Gord King that they would be naming some streets, a pond, and a gate after him in the Keswick neighbourhood after Gordon King.

King had been part of The Great Escape, a celebrated break-out from a German prisoner of war camp. The following story about King, written by former reporter Jeff Holubitsky, was originally published in the Edmonton Journal on Nov. 11, 1999.

Stalag Luft 3 prisoner Number 209 had beaten the odds again.

In the spring of 1944, he was the 146th Allied airman to win a chance at freedom through the escape tunnel 10 metres below the prisoner of war camp in Germany. By a quirk of fate, he never had his chance in the tunnel before it was discovered. And by good fortune, he was not one of those who paid for the escape with their lives. ”I was lucky I wasn’t anywhere near getting out,” Gord King says in the comfort of his west-end bungalow, 45 years later.

Lucky he not only survived, he thrived. King returned to Canada where he raised a family of championship curlers, including daughter Cathy Borst. ”I happened to look through an old high school year book that listed the fellows who were killed and it’s hard to believe,” he says. ”In the air force, the odds weren’t that great. …”

”I’m very fortunate to be here today and thank God for it, because when I think of the guys who didn’t make it, it’s tough because they were all young guys and had their lives ahead of them. ”As far as another war, forget it. We just can’t let it happen.”

Two years before the daring escape attempt, he had bailed out of a burning bomber over Nazi Germany. He’d been a prisoner ever since, half a world away from his sweetheart, June, in Winnipeg.

Only 76 made it out through the narrow tunnel which stretched more than 100 metres — past barbed wire and guard towers — before it was discovered by a guard who had stopped to relieve himself when he noticed steam rising from a hole in the March snow.

”I was in a room with a bunch of other guys waiting my turn,” says King. ”I was excited, but when the thing got discovered there was real pandemonium.”

The men all carried rations of raisins and biscuits to provide sustenance for a few days. ”We ate those in a hurry and got as sick as a dog.”

Unfortunately after a year of immaculate and secret planning and construction, the escape route fell a few metres short of a forest. King had to remain in the camp where he’d been since he was shot down in 1942.

Of the 76 who made it out, three — two Norwegians and a Dutchman — made it home.

Seventy-three were recaptured. Twenty-three were sent back to the camp.

Fifty, including half a dozen Canadians, were gunned down.

Only 50 were ‘murdered’

The Great Escape, as it was called in a 1963 Hollywood movie, enraged Adolf Hitler. He ordered that 100 PoWs pay with their lives.

Joseph Goebbels, his propaganda minister, convinced the Fuhrer such a move might incite repercussions against German prisoners in Allied camps and Hitler cut the number to 50.

”They loaded them into trucks to supposedly bring them back to the camp,” King remember.

”When they were travelling they let them out on the side of the road to relieve themselves and just machine-gunned the men in the back.”

”They were murdered, they weren’t executed.”

Today, the ashes of those officers lie silently in a memorial on the site of the Second World War camp as the number of surviving veterans of Stalag Luft 3 grows smaller year by year.

Gord King hasn’t spoken about his experiences often.

Compared to the sacrifices of others, he doesn’t rate his contribution very highly.

But he also doesn’t want young Canadians to forget what his generation accomplished all those many years ago.

This year he attended a national prisoner of war reunion in Ottawa. He thinks it will be the last time they celebrate together, but even so, the former PoW appears almost embarrassed to draw attention to his experiences.

”The guys who weren’t prisoners of war, that did their job, that made their trips, they have reunions too and they don’t seem to get the recognition we get.”

Romantic idea of war

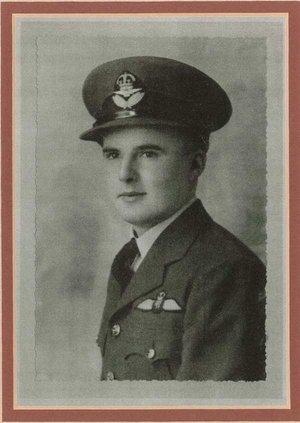

Stanley Gordon King was born in Winnipeg 79 years ago. His dad was already a Stanley, so the younger King with a keen interest in sports became Gord.

With the war already raging in Europe and the romantic idea of flying filling the head of a prairie boy, he signed up in September 1940.

”I wanted to be a pilot, but when I went they said they had too many pilots so I wanted to be an air gunner because I was small.”

Nearly 60 years later it’s tough to believe anybody would want to sit in a small glass dome under an aircraft, but the Royal Canadian Air Force also had too many gunners.

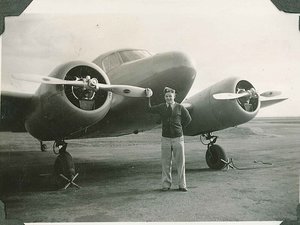

King was assigned to operate a radio. However, during training he was on a hockey team and did some boxing and became friends with a doctor who pulled some strings and got King into flight school in Regina and Saskatoon.

In October 1941, he was sent to England were he finished bomber training and took a leave he’d never finish. He was called back after a 1,000-plane attack on Cologne had baffled German defences and was considered a huge success.

”They decided to do it again and put every plane they had in the air including our training planes,” says King, who was by then a 22-year-old flight officer in charge of a well-used Wellington bomber.

”They really weren’t first-line planes, but we figured it would be a piece of cake, so off we go.”

With the burning city of Bremen within view, a German nightfighter caught the plane in its sights.

”Partly from the fact that we couldn’t get our plane over 10,000 feet and we were green and inexperienced, we probably didn’t keep as sharp a lookout as we should have and we got shot down.” King and his crew bailed out. Two of the five men would survive. During the long flight, King had undone the shoulder straps of his parachute to relieve muscle tension.

”In the panic to get out I forgot to do them up again and got hung by my legs, and so I came down upside down.”

He landed in a tree in complete darkness. Struggling out of his harness, King plunged to the ground, knocking himself out. In the morning he awakened with the prod of a farmer’s pitchfork.

King was sent to a camp and would remain a prisoner of war until just before V-E Day, nearly three years later.

”They were ready for us and knocked a lot of planes out that night,” he says. ”So my war effort was meagre and I’m not proud of that, but it happened.”

As the war continued, the numbers at Stalag Luft 3 swelled. When King arrived there were probably about 600 Allied airmen, and the prisoners were pressed into building a new camp for a population of 1,500 to 1,600.

They had come from around the world — Great Britain, Canada, New Zealand, Poland, Europe, Australia — and every walk of life.

(Americans were sent to a camp of their own and, despite the movie, never took part in the escape.)

”It was excellent,” King says of the Allied camp. ”New buildings and new everything.”

Food rations, though, were meagre and without Red Cross parcels from home, King believes prisoners would have starved to death on a constant diet of ”barley glop and turnip soup.”

His own weight dropped from about 61 kg to 50 kg at the end of the war.

”The people in this camp were like a little city,” says King. ”All the trades — electricians, carpenters, plumbers, lawyers, doctors, tailors, musicians and professional actors who put on marvelous plays.

”And from that nucleus of talent they decided that rather than have individuals try to get out, which we did for the first few months … and none of it worked, so they decided we’re going to organize this thing right.”

Everybody did something

Besides constant searches and two roll calls a day, the German guards left the prisoners alone to run the camp by themselves and also plan the escape. ”Everybody in the camp knew what was going on. Nearly everybody did something because there were hundreds of jobs you could do.”

Old uniforms were transformed into civilian suits. Graphic artists created fake identification, passports and railway tickets. A hard-rock miner from Canada taught the men how to build tunnels.

What the men didn’t have, they bribed guards with cigarettes and Red Cross rations to get — such as cameras and film to take fake ID photos.

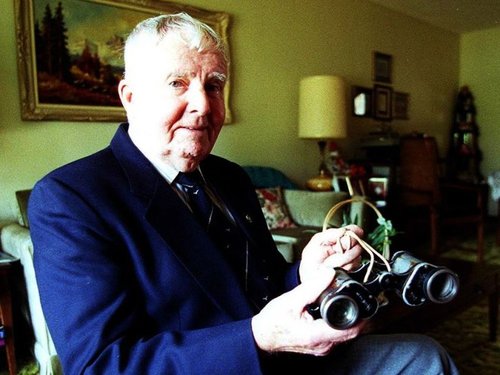

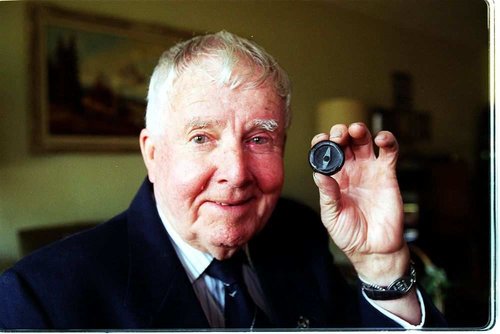

King still has some mementoes of those days. He pulls a small black cylinder out of the soft protection of an old Crown Royal bag. It’s the compass he was issued days before the escape.

The casing is moulded from a melted phonograph record. The diamond shaped direction pointer shaped from a razor blade. Surprisingly, a swastika design is pressed into the back. Prison camp humour.

”It was made in Germany,” chuckles King.

To their captors, the prisoners spent their time putting on plays (King has pictures of himself playing a woman), giving classes in history or literature, reading hundreds of novels, playing in the band, or participating in sports.

King played baseball, soccer, cricket and, when the weather was favourable for ice, he was goalie on a hockey team.

In fact, his parents who led a home-front movement to supply prisoners of war with the things they needed, received a commendation on King’s behalf from the YMCA for their son’s efforts in organizing leagues and teams. The activities helped pass the years of confinement with really, little to do.

King remembers an Australian who couldn’t take camp life. Once, when he slashed his wrists, King and his buddies made sure he was patched up. About six months later the man made a break for the fence in broad daylight. His friends among the prisoners rushed tell the guards that the man had gone crazy. But it was too late. He was shot before their eyes.

While all of this was going on, the prisoners were also working on three tunnels. One was discovered by the Germans, one was used for storage and the third provided the brief chance at freedom.

King was put to work manning an air pump 10 metres below ground. It was made from old knapsacks and dried KLIM (milk) tins and provided fresh air for the diggers.

The tunnel, about a metre wide by a metre high, was constructed in sandy soil and bed boards were used to shore up the walls. Access was through a hollowed out chimney base beneath the stove in one of the cabins. The stove was moved with special handles, the workers went down the hole, and the stove was replaced, concealing what lay below.

Tons of sand to hide

The biggest problem was the disposing of the sand.

”So we had these fellows called penguins,” says King, who was often a penguin himself, walking stiff legged with sacks of sand hidden inside his pant legs.

Once he’d waddled to the sandy sports field, he’d pull a drawstring attached the bottom of the sacks, releasing the soil.

”We raised the level of the field by six inches,” he laughs.

The tunnel took about a year to complete. The first 30 or so men picked to escape were those thought to have the greatest chance of success, such as those who spoke fluent German.

He remembers the Dutch airman, the first out of the tunnel, coming to say goodbye, dressed in a black suit with a Homburg hat. The former medical student even had a doctor’s bag complete with stethoscope. He was one of the lucky ones who got home.

But within a year the war would be over in any case. King remembers hearing the Russians’ guns less than 40 km away as he played his final hockey game.

The Germans evacuated the prisoners, marching them north to different locations until the guards simply gave up.

”They knew it was over anyways,” says King, who ended the war by taking a couple of prisoners while walking down a country road. A couple of heavily armed German soldiers, fearing for their futures at the end of the war, handed their weapons over to an unarmed King and a friend.

King arrived in London on May 8, 1945, V-E Day.

After the war, King returned to Winnipeg to his fiancee, June. They’d been together since the age of 14 and are still married.

”She’s the only girl I’ve ever loved,” he says.

During his PoW years, she sent him hundreds of letters.

Now retired, he worked for a flooring wholesale company and moved to Edmonton in 1965.

Not surprisingly, his kids were keen in sports, two sons became junior Canadian curling champs and his daughter, Cathy, skipped the Canadian women’s curling championship team in 1998.

At the recent convention of his PoW organization, the remaining former prisoners began a campaign to promote a composite picture of the Stalag Luft 3, the memorial to the slain air force officers, and the tunnel.

”What we’re hoping to do with this picture is keep the memory of, not only the 50 who were shot, but of all the airmen who were killed in the war, and get one of these pictures in every Legion and war museum across the country.”

Lest we forget.

The City of Edmonton is honouring a Second World War veteran and longtime community volunteer by naming a small area in the city’s Keswick neighbourhood for Stanley Gordon King.

EDMONTON JOURNAL - AINSLIE CRUICKSHANK

“I was surprised and very proud to have something like that named after me,” said King, 96.

He added he wasn’t sure why he got it.

King served in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the war. Miraculously, he survived when his plane was shot down over Germany in 1942, only to be captured and taken to Stalag Luft III as a prisoner of war.

There, King was part of what’s now known as the Great Escape, thanks to a 1963 movie, helping to dig three tunnels out of the camp. On the night of the escape, King was supposed to be the 141stprisoner to make the journey out, but the tunnel was discovered before he got his chance.

Most of the men who escaped were recaptured and 50 were later shot by Hitler’s order.

Their deaths weighed heavily on King, said Bud Squair, a member of the City of Edmonton’s naming committee who brought forward King’s name for consideration.

”I’m very fortunate to be here today and thank God for it, because when I think of the guys who didn’t make it, it’s tough because they were all young guys and had their lives ahead of them,” King told the Journal in 1999.

Squair, who met King at the retirement home where they both live, said he wanted to honour King for both his wartime and peacetime service.

While the portion of the Keswick neighbourhood, which is in the Windermere area of Edmonton, named for King is still a couple of years away from development, Squair wanted to push the process forward, given King’s age. He will lend his name to four roads — King Road, King Vista, King Landing, King Wynd — a pond and a gate.

King’s daughter, Cathy, was both “proud” and “thrilled” to see her father honoured.

“Good things happen to good people and he is one of those good people,” she said.

Born in Winnipeg in 1920, King, who goes by his middle name, and his family moved to Edmonton in the 1960s, where he worked as the western regional manager of a flooring company until he retired in the 1980s.

Cathy remembers her father having his staff to work in their family home after a huge fire destroyed the company’s building in the 1970s — just another example of his perseverance in the face of challenging circumstances.

He was an active volunteer, as a member of his church, the Rotary Club and the Freemasons, and an avid curler until just a few years ago, Cathy said.

Her father also served as the president of Edmonton’s chapter of the Ex-POW Association, where he helped organize monthly meetings and social gatherings in the city, as well as an international gathering of former prisoners of war in Calgary in 1983.

In 2006, he received the Minister of Veterans Affairs Commendation, which is awarded to people who have made exemplary contributions to the care and well-being of veterans.

Minister of Veterans Affairs Commendation - 2006

Mr. Gordon King is a Second World War Veteran and former POW. In the 1950s, while residing in Winnipeg, a group of Veterans formed an Ex-POW Association of which Mr. King belonged. Upon moving to Edmonton in 1965, Mr. King began contacting fellow ex-prisoners of war, and together they formed the Edmonton Branch Ex-POW Association, of which Mr. King currently serves as President. The Edmonton Branch assisted the Calgary Branch, who in 1983, sponsored an international reunion of former POWs from all Commonwealth countries. Considered to be an excellent leader, Mr. King has organized monthly meetings and social occasions for his membership. In recent years, he has had to devote more attention to the well-being of Veterans and their families, arranging for hospital and home visits. The need to help his comrades increases as time goes by, and he does not lack the energy to lend a helping hand whenever needed. Mr. King continually demonstrates compassion toward his fellow Veterans and their families by keeping in touch in between monthly meetings and luncheons.

The Memory Project - Veteran Stories:

Stanley C. Gordon “Gord” King - Air Force

Supermarine Spitfire IXE aircraft of No. 412 (Falcon) Squadron, RCAF, preparing for takeoff.Credit: Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-136915

Credit: Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-136915

"When I woke up, there was a bunch of farmers around me with pitchforks telling me in German, “For you, the war is over”."

I joined up in September of 1940. And around that time, we were not doing very well. So I figured, I’d better get in there and help them win this war. So I joined up in September 1940 and trained to be a pilot. Well, you go through various training, land training, flight training, then you get posted overseas and you take more training. And then eventually, you get posted to a squadron, which I did get posted but before I got there, they decided to put on a special 1,000-bomber raid. And to get 1,000 bombers in the air, they had to use all the planes they had, which included training planes. So I went over in one of our own training planes. And I wouldn’t blame the planes so much as being green and not knowing what’s going on and German night fighters spotted us and shot us down.

Well, we all bailed out and we didn’t all get out, two of my fellows didn’t get out and I landed in some trees and I slipped out of my parachute and I was pretty high up in the trees and I knocked myself out when I hit the ground. When I woke up, there was a bunch of farmers around me with pitchforks telling me in German, “For you, the war is over”. And it was, and this was in June 1942.

I got picked up by the German Luftwaffe [air force] and taken to a prison camp and stayed there for a couple of weeks, then got transferred to a major officer’s camp called Stalag Luft III [a prisoner-of-war camp for air force servicemen]. Well, this was a brand new camp. It was built specifically for officers and I was a Flying Officer at the time. So I got into this new camp and brand new and the huts were brand new and it was a very nice camp, as far as you think being in a prison camp is nice. But I got there and spent the next three years there until the end of the war.

Well, they pretty well left us to our own. We had two or three roll calls a day but during the day, we were left to our own and so we did what we wanted to do. We played sports, we took classes, we had people in there from all walks of life, doctors, lawyers, teachers, so you could learn things if you wanted to. The main objective was to get out, so we started to dig tunnels, tunnels to dig out underneath the wire and get out. And at Stalag Luft III, we started three tunnels with the idea that if one had got discovered, we could keep on digging the other ones. Finally, about March [1944] , the last tunnel was dug and we broke out and we got 70 officers escaped through that tunnel. Most of them were caught and 50 of them were shot. The most terrible thing that could happen, which was against all Geneva Convention rules but Hitler was so upset that we could do this and he [ordered] shot 50 of our officers, a lot of Canadians.

And fortunately, though I was drawn to go out, we felt we’d get a couple hundred out, we got 70 out. My number was about 140, so I never did get out - which probably was lucky.